Achieving optimal efficiency and performance is crucial for the design of propellers. A combination of AI and CFD helped win a recent online propeller design competition hosted by Daniel Riley, a maker and popular YouTube creator (RCTestflight). Using CAESES and AirShaper, we generated two high-performance propellers that demonstrated remarkable efficiency.

Objective

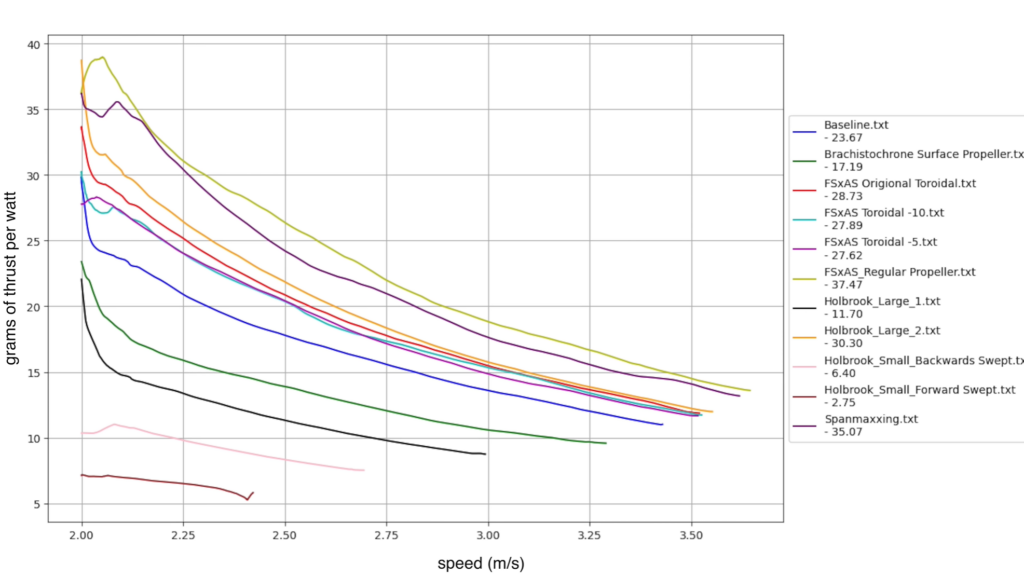

The primary goal of the competition was to design propellers that could achieve maximum efficiency across a wide range of operating speeds. Using an experimental approach to evaluate the performance, Daniel from RCTestflight 3D-printed the propellers and attached them to a test vessel. He came up with a unique efficiency parameter that consisted in measuring the (grams of) thrust per Watt of each propeller from 2 m/s to whatever speed the boat reaches at full throttle (mostly around 3.5 m/s). The propeller with the largest integral, i.e., area under the curve, wins. This comprehensive approach provided a more thorough evaluation of propeller performance compared to traditional single-point objectives, making the challenge both complex and rewarding.

As toroidal propellers have become a popular topic, we decided to run separate optimizations for a toroidal and a conventional design, so that we could benchmark these two types against each other.

Propeller Optimization Approach

In short, a large number of geometry variants were generated by CAESES and analyzed by AirShaper. The results were fed into a machine learning model, which was then used to predict the best possible design.

This process involved several key steps:

- Parametric Model: We developed a parametric model for each the conventional and toroidal propeller using the CAESES CAD modeling environment.

- Design Space Exploration: We sampled the design space using a Design of Experiments (DoE) approach utilizing a Sobol sequence.

- CFD Simulations: Using AirShaper’s API, which seamlessly connects CAESES to the CFD tool, we ran the simulations at different speeds for each design

- Machine Learning: We used the CFD results (torque and thrust) within CAESES to train surrogate models. With these surrogate models, we are able to generate the open-water diagram for any design variant in the considered design space.

- Optimization and Validation: With the information from the open-water diagram, each design can be evaluated over the whole operating range and the single objective function can be evaluated. A gradient-based optimization was used to find the optimal design.

Parametric Models of the Propellers

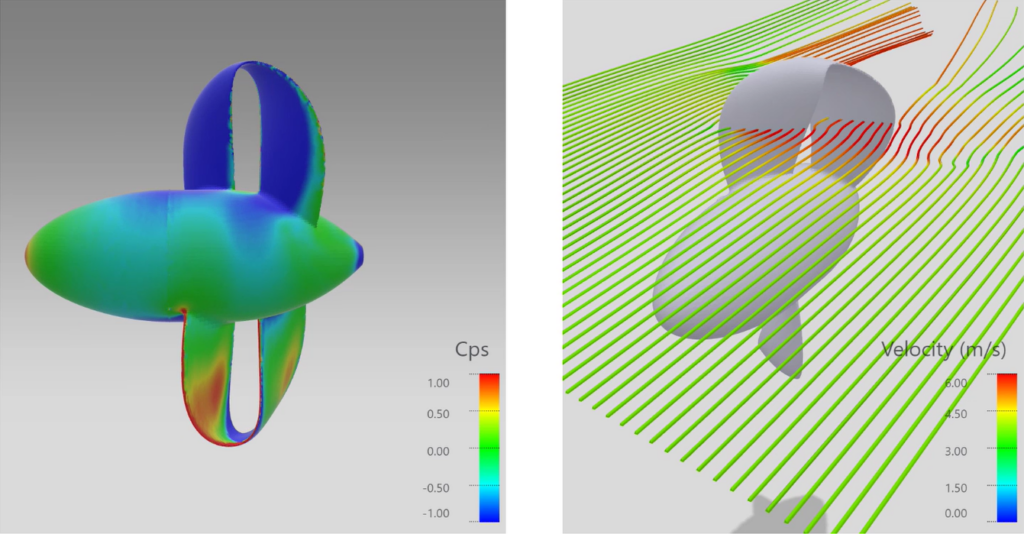

Two separate parametric models were created for the toroidal and conventional propeller. Of course, several parameters can be used to control their shape. For the design exploration, 6 parameters for each of the propellers were selected, shown in the following animations (click on the images to see them in higher resolution).

The ranges for these parameters were determined by realistic operational ranges (e.g., avoiding pitch angles that would lead to stall) and physical constraints (e.g., structural integrity, geometrical interferences between blades, and maximum diameter).

Toroidal Propeller

Conventional Propeller

CFD Connection and Optimization

Through the provided API, CAESES was able to communicate directly with AirShaper to launch simulations for each design variant and obtain the resulting torque and thrust values. This integration greatly improved the efficiency, streamlining the process of uploading models, defining parameters, and retrieving results.

The results from AirShaper were read back into CAESES to create surrogate models for thrust and torque at three different speeds. By interpolating the output of the surrogate models, we were able to create the curves for the thrust and the torque coefficient over the advance ratio. Having this information, and knowing the vessel’s resistance for any speed, we were now able to easily calculate the propeller efficiency over the whole operating range for any design in the design space without running a CFD simulation. Therefore, the actual optimization runs could be carried out in just a few minutes instead of hours or days, which is the case for a direct optimization approach where each design has to be evaluated by a CFD simulation.

Results

For the toroidal propeller the optimization resulted in a 21% improvement over the baseline propeller, which was loosely based on FRIENDSHIP SYSTEMS’ Wageningen B-Series App.

For the conventional propeller the optimization resulted in a staggering 58% improvement over the baseline propeller! And even as new and improved designs from the community came in, this design still had a 7% higher efficiency compared to the second best 3D printed design in the competition.

Toroidal vs. Conventional Propeller

The optimized conventional propeller, featuring slender blades and a maximized diameter, outperformed the optimized toroidal propeller by 24%. However, this is not necessarily a conclusive assessment about whether conventional or toroidal propellers are better and we believe this is very much dependent on the specific application case and requirements a design is targeting. But it does show that the design of a good conventional propeller is easier than the design of a good toroidal propeller. Especially, when limiting the simulation resources, the apparent advantage of having more degrees of freedom with the toroidal propeller might become a disadvantage, as the number of variable parameters has a direct influence on the number of simulations needed to achieve a sufficient exploration of the design space.